As promised in the last Hopecology newsletter, I’m continuing the exploration of I-me-mine mindset: what about ideas? Or the land itself? In poring over these questions the last two weeks, a soundtrack once again appeared. It revealed that a step further from the I-me-mine mindset—both more powerful and dangerous—is Us and Them.

Us and them

And after all

We're only ordinary menMe and you

God only knows it's not what

We would choose to do"Forward", he cried from the rear

And the front rank died

The general sat and the lines on the map

Moved from side to sideBlack and blue

And who knows which is which

And who is whoUp and down

And in the end

It's only round and round, and round…

Down and out

It can't be helped

But there's a lot of it aboutWith, without

And who'll deny

It's what the fighting's all aboutOut of the way it's a busy day

I've got things on my mind

For want of the price of tea and a slice

The old man died

Though the song had played in my head many times before, I hadn’t really taken the time to ponder the lyrics until this week. What timing, as they seem to be pointing toward a sense that something being fought over is not worth the fight’s cost.

Mirroring the Derry Girls

Last week I watched the series finale of the Derry Girls, a British teen sitcom set in Northern Ireland in the 1990s. The final episode features a voiceover monologue as the show’s main characters each, in turn, go to the polls to vote in the Good Friday Agreement referendum. The agreement would end most of the violence of the Troubles—an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that had prevailed since the late 1960s.

The vote took place in May 1998, the same spring that I walked, in white cap and gown, across the stage in my high school’s over-optimistically sized football stadium. In the show, the kids are turning 18 and voting for the first time in the referendum. The Cranberries’ Dreams plays in the background during the protagonist, Erin Quinn’s, monologue:

There's a part of me that wishes

everything could just stay the same.

That we could all

just stay like this forever.

There's a part of me

that doesn't really want to grow up.

I'm not sure I'm ready for it.

I'm not sure

I'm ready for the world.

Crime is crime is crime.

It is not political,

it is crime.

But things can't say the same,

and they shouldn't…No matter how scary it is,

we have to move on,

and we have to grow up,

because things...

well, they might just change for

the better.

So we have to be brave.And if our dreams

get broken along the way...

...we have to make new ones from

the pieces.

Erin is talking about turning 18, having the right to vote, and facing the messiness and scariness of adulthood. But she is also talking about the referendum, which, in order to kickstart the peace process, required major concessions from both sides.

It resonates with a conundrum I face somewhat frequently: Do you want to be right, or do you want to be happy? In the referendum, the question was put to the people of Ireland and Northern Ireland: Do you want your righteous indignation, or do you want peace? Of course, the Troubles weren’t that simple. Nothing is. But when it comes down to a single yes-or-no choice, simplification can help us decide.

This is not an easy question. I choose my righteous indignation, at least mentally, most days. It’s easier. It feels more natural, and perhaps it is, because it’s the reptilian brain doing what it does best.

But this is the beauty and hope of being human and not a reptile: we can choose to use the rest of our brain, and broaden our vision and perspective to accept the both/and. It’s hard, it’s not ideal, it’s never perfect or pretty or easy. But it is an option.

Drafted for the opposing team

Once, I was invited to participate as a pinch-hitter of sorts in a project at the last minute before a scientific manuscript was submitted. I should have been flattered; after all, the researchers saw the need for my specific expertise and asked for my help.

But I was frustrated that I hadn’t been asked sooner, because the manuscript had some substantial holes in its logic and arguments, holes that made me fear what the manuscript could do (devastating things for the species involved) once the paper was published if they weren’t remedied.

Once I read the draft, I wanted to say, No, you’re on your own, you should have asked me sooner.1 But the paper would be published regardless of my involvement; so wasn’t it on me to help them get it caveated as much as possible before it was put out into the world? As Erin Quinn said, a crime is a crime. But do I want peace?

In this case, for me, peace meant what’s best for the species, and that meant fixing things that were broken, because I have the expertise to lend to such an endeavor. Like Erin’s coming of age story, I was learning to face a new level of reality in academia at the time.

Not all science is flawlessly planned from the get go: it’s messy, and people are motivated by myriad other things besides the advancement of science, technology, and progress. Much—if not most—of science is motivated by, or implemented because of, politics, money, and power.

Does this surprise you? I know it’s very comforting and convenient to put science on its own pedestal. Have you noticed, though, how anything, once put on a pedestal, gives one a better view of its, um, under parts? Though society likes to uphold science as above the pursuit of money and power, it’s really and truly not. Not anymore, if it ever was.2

Whose knowledge?

Corruptibly flawed academic reward system aside, I was faced with a conundrum because I couldn’t quite see clearly my moral and ethical responsibility. When I gave my mind a break from the problem to meditate on something else, I was reminded of interdependence. I both am and am not the owner of my knowledge. I may choose to use and integrate that knowledge in my own unique way, but is it ever really mine?

Sometimes when I have an idea for something to write about, I think, No, I should save it for my book; what if someone (or, more likely, AI) reads it and then steals my idea and runs with it and takes the credit? Annie Dillard, in The Writing Life, gives the best advice for when these selfish (and they are selfish, even if under the guise of self-preservation) ideas settle upon us:

Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes3.

I stand on the shoulders of giants, as they say, with the science I’ve advanced having been built upon the work and knowledge and publications of those who came before me. I’ve also had generous mentors, teachers, and guides. Yes, I have worked my ass off for my knowledge and wisdom and PhD. But none of these things appeared in a self-made vacuum.

In her book, Big Magic, Elizabeth Gilbert describes having the idea for a book, and then not having the time or bandwidth to write that book, then a writer friend of hers—some months to years later, after she had forgotten all about it—tells her she is writing the EXACT same book. Gilbert writes,

I believe that inspiration will always try its best to work with you—but if you are not ready or available, it may indeed choose to leave you and to search for a different human collaborator.

In this sense, we are only the vehicle. If I walked away from the project, the researchers likely would have found a different human collaborator.

But, to me, precisely because my unique combination of wisdom, knowledge, experience can serve the function of making science being birthed into the world better, more rigorous, and safer in its application, then it ought to. Which means I had to get over my idealist projections of how the research should have been done, and help to make it as good as it could get, now that it had been done.

The methods were sound; but the assumptions underlying it were flawed. Without a species expert helping to plan the project and the analysis, this was bound to happen. But if could help bend it, even a little bit, toward helping the species that the research unabashedly capitalizes on for the researchers’ personal gain, then I had to.

For the sacrificial frogs

Last weekend I attended a conference online, where researchers reported the results of their amphibian research. I have attended many of these conferences before. I used to look forward to them: the excitement of new ideas and cutting-edge research and putting forth my own work amidst it all.

But now, as I look at the endless slides, and the experiments that seem to repeat each other over and over with only small details changed between them, everything is overshadowed by the suffering the frogs are put through, simply for the collection of data, and for increasingly small gains for conservation.

A graduate student cheerfully reports how many frogs in their experiment died from exposure to one treatment or another. Everyone nods and giggles at the jokes, carefully placed to lighten the mood. We have all convinced ourselves that this is the best course of action, still—that the advancement of the front lines of knowledge is worth the sacrifices required. If we hadn’t convinced ourselves of that, we wouldn’t be here.

That these conferences hit differently for me now than they used to signals a shift in me, but it does not change the fact that these kinds of experiments helped advance my career. I didn’t do exposure experiments myself—my research was only field-based—but my research benefited from the knowledge gained by others’ exposure experiments.

These long-lost frogs: they are the giants whose shoulders I stand on. They were sacrificed for knowledge. This is why I have to act when given the choice, however imperfect the options may seem. In a way, my knowledge belongs to them, too; it is interdependent upon their lost lives; so it only seems right that I should offer that knowledge toward the continuation of their kind.

The ninja turtle at the tea party (the Alice in Wonderland kind; not the Sarah Palin kind)

So what happened with the research paper? I decided to act, to participate and contribute, as it was my responsibility, no matter the professional cost. I took the time to make a clear argument outlining my concerns, one by one. As I did this, I felt the energy rise in my body; adrenaline gearing up for a fight, perhaps, as academics tend to have tender egos and I did not anticipate my criticism would land well.

I expected to be defended and argued against, and readied myself to have my invitation to collaborate be retracted. I delivered my arguments and concerns clearly. Then I waited. And waited. And waited a little longer. The longer I waited, the more I expected the worst, so continued to mentally armor up, readying my next line of defense.

When the response came, they were grateful for my input, glad I had pointed out things they hadn’t been able to see from their own viewpoints and knowledge bases, and committed to addressing them in the ways I suggested.

All of the armoring I had done in preparation—for this unexpected response—made me feel like I had just shown up for a tea party dressed like a ninja turtle. I had “them”-ed them, and hadn’t even realized it. Their response made it clear that we really were on the same team, and came as an enormous relief. What I had originally seen as a double bind really wasn’t one at all. Sometimes the only war is the illusory one in the mind.

This land is…whose land?

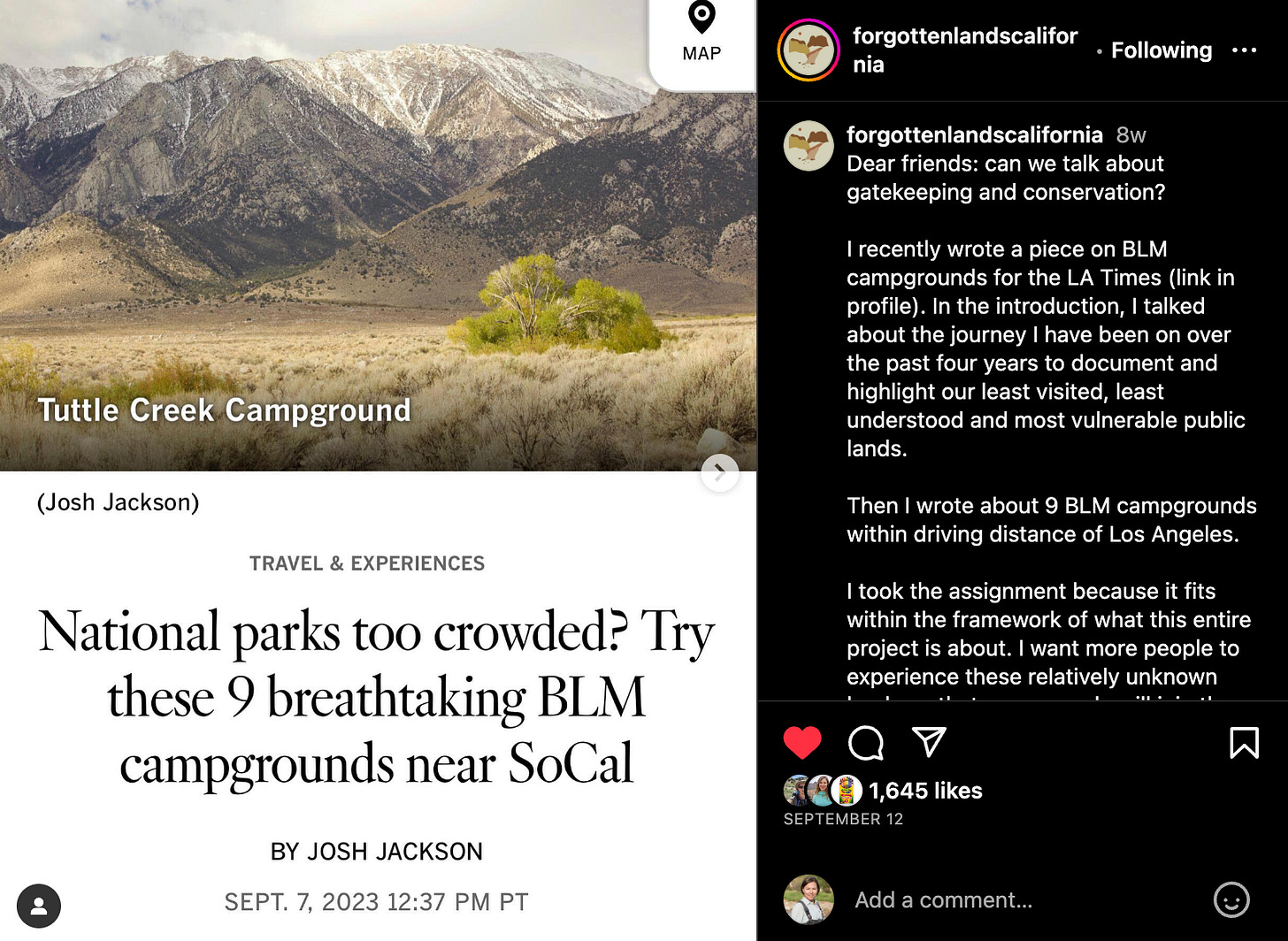

Not long ago, a social media account I follow because it extolls the beauty and accessibility of lesser-known Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands posted something different. Josh Jackson, of @forgottenlandscalifornia, announced that he had just published an article in the LA Times highlighting several BLM sites to explore. I felt a little twinge of worry, and retreated to the comments to see if it was just me. Nope.

“Welp, there it goes.”

“Going to cross these off my list.”

The comments signaled that the BLM lands lovers were all for wide open spaces and public lands, but only if they were for the personal use of them and people like them.

This was an actual comment:

“But they aren’t like us. They will just trash the place.”

At that point, I added a comment admitting my initial reaction, but noted that we have to garner more support for BLM lands, because what we don’t use (and share, and love, and support, and vote for), we lose. This is the whole purpose of @forgottenlandscalifornia in the first place.

The comments continued to escalate, so I dropped a direct message to Josh, offering support and reminding him that he was doing the right thing for the cause, even if it upset some of his followers.

What surprised me is how unabashed these BLM lands lovers were about us-and-them-ing public lands users. I don’t know why I was so surprised. I guess because the fictional “us” in my mind was public lands lovers writ large. At the same time, my initial twinge of worry had the same root as these haters. I know what they mean. I’ve been to beautiful landscapes that, in some places, look more like dumping grounds than wildlife habitat. It’s heartbreaking to see the land so used and abused and misunderstood.

What I pointed out in the comments on the original post, was that I was once, too, a person that littered. I had not yet learned Leave No Trace ethics. I needed to be taught. But in order to be taught, I needed to show up to beautiful places. I needed to be shown them by someone else. And those places needed to be there for me to experience them, connect with them, then care about them, then realize that the way I cared for them would affect their health; that I didn’t live in a human vacuum. Only then could I change my behavior. I was given that chance. I want other people to have that chance.

Josh took down the post, responded kindly to my direct message of support, and after a period of reflection, created a new post with a response. He nailed it. He was not going to let the us-and-them mentality take over, and called out the culture of gatekeeping that the initial post had unearthed. Like my manuscript conundrum, he had returned to his values in a moment of conflict, and then acted wisely to create a shift in the culture at his fingertips, in a way that only he could.

Shine on you crazy diamond

Have you seen the new Elvis movie that came out last year? I just watched it for the first time last night because everyone I know who has seen it spoke very highly of it, and I was curious. I am also currently enjoying steeping myself in a better understanding of the 1960s while reading Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

If you have seen the movie, you may have walked away from it with a sense of loss from what fame, fortune, and drugs seem to do to so many talented people who become our beloved cultural icons.

But what struck me most about the movie was that Elvis had a unique combination of experiences and talents that moved him to perform in a way that only Elvis could. He tried toning down his moves when implored to, but he couldn’t do it without feeling awful about himself.

Life had no spark until Elvis could be Elvis again. So he came back and did exactly what he wanted to do, and fans couldn’t get enough of it. He was on fire. Precisely because he did what had never been done before, he was able to overhaul rock and roll music, and culture, and social norms. He figured out what made him come alive.

*Cliché content warning*

You know that quote by Howard Thurman that is beautiful but is repeated so much it’s become, sadly, cliché? Here it is, again:

“Don’t ask yourself what the world needs. Ask yourself what makes you come alive, and go do that, because what the world needs is people who have come alive.”

I don’t think Elvis was asking what the world needed when he decided to go on the road and try to make a career out of performing. He just did it because it made him come alive, and, in the words of Joseph Campbell, he followed his bliss. The outcome—the way it changed music and society and culture—was out of his hands.

Though Elvis’ death at 42 was tragic, he served his purpose, because he did exactly what only he could do. This is what gives me hope today: the story is not over. The excitement I felt when I donned the metaphorical ninja turtle accoutrements wasn’t the adrenaline of righteous indignation; it was the adrenaline of purpose—the joy of doing what I am meant to do; the same feeling, I imagine, that made Elvis do Elvis.

If Elvis, Josh and I can figure out our own unique fingerprint of right action in day to day life, so can you, and so are millions of other people. Every single day we have choices that can ripple out and foster change. We have to do these things, however trivial they may seem to us. They are not trivial. They are our purpose in the world.

What makes you come alive today?

Food for thought via a gem I heard this week: “Should” is just “could” with shame on it.

For a fascinating overview of the evolution of peer review (inherent in the scientific process as we know it today), I highly recommend this impeccably researched and eye-opening post from

in : The rise and fall of peer reviewYou can thank Annie Dillard that this post is longer than usual, as I fight the urge to save (hoard?) sections of this post for future newsletters.