I have an intense love for travel: a very essential part of me feels unmistakably at home on the road, wherever it is. I am somewhat addicted to the joy of being completely removed from much of what is familiar. Is it always joyful? No. Traveling is actually quite inconvenient sometimes. But its return on investment through mind-bending shifts in perspective and learning new ways of seeing the world is priceless.

I’ve been fortunate to travel to India, Nepal, Thailand, some of eastern and much of western Europe. I’ve lived in Canada, Mexico and Nepal for months at a time. I’ve crisscrossed the continental US on solo road trips so many times I lost count. All of these experiences had one thing in common: they radically changed the way I see the world and my home country, and often turned upside down my perceptions of, well, just about everything. Even the time I spent living in Canada—which, to be sure, is a lot more like the US than most other places—taught me a lot.

I lived in the north woods of the province of Ontario for most of 2004. As you drive into the town of Ear Falls, the sign informs you that the population is about 995. So, when I arrived to join a Canadian PhD student studying Boreal Owls under night skies frequently graced with skeins of the Northern Lights, there was a little hubbub. Strangers approached me, saying, “So—you’re the owl girl.”

Indeed, I was the only woman in town who worked with owls, with the extra oddity that I was an American. When I replied, “Yeah…I guess so,” and eventually just, “Yes,” sometimes the response was, “You don’t sound like an American.”

“What does an American sound like?” I would ask.

“George Bush.”

You may recall that in the summer of 2004, there was a big election coming, and then-president George W. Bush was getting a lot of airtime.

He was not popular in Canada. When the election finally came, I voted absentee in plenty of time for my ballot to get back to my home state. Yet, for a while after the election, I was very unpopular.

Fresh out of undergrad, I thought I knew the way the world worked. My experiences in Canada quickly taught me that the idealism I’d been steeped in had led me astray. I worked alongside fur trappers (who were capturing our study animals) and feller buncher operators (who were removing the forest we were trying to understand), whom I had been taught should be my sworn enemies. But as the people of this place—who lived closer to the land than anyone I had ever met—taught me about the natural history, cycles, and rhythms of the Boreal Forest, I never saw or approached conservation the same way again. They are the wisdom keepers, and I was fortunate to have lived and worked with them as they freely shared with me the way they love and care for their wild and beautiful home.

I’m currently exploring Ireland on the first leg of a trip that entailed days of packing, weeks of preparing, months of planning, years of saving, and decades of dreaming. What follows are just a few highlights of some of the stretching my mind has been doing over the past week.

Coming from North America, my frame of reference for what is taught as history is, generally, exceedingly recent compared to Europe.1 In Ireland, I can pull over and explore a 15th century abbey on a whim. Relics of the Stone Age abound. Antiquity begins to blend history, myth, and legend to a point where it’s not clear which is which. After gazing at astonishingly preserved medieval bestiary frescoes on the ceiling of a 15th century abbey for so long I have to hold the back of my head up with my hand, I find myself beginning to wonder if dragons had, indeed, been real when artists had painted them alongside hares and other native wildlife. Observing that thought come and go, I consider whether I am losing my mind. I conclude that, instead, it’s bending, and like yoga for the brain, that’s a good thing.

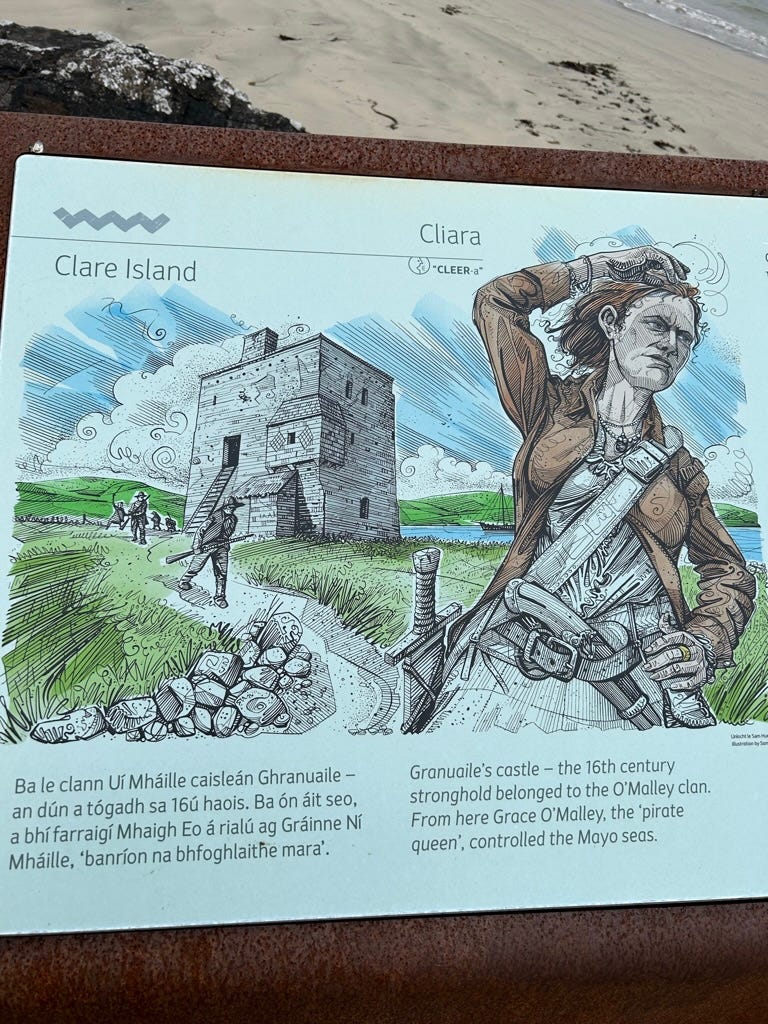

On the West Coast of Ireland, Clare Island sits in Clew Bay, the historical territory of the legendary Gráinne Ní Mháille, (anglicized: Grace O’Malley or Granuaile), the Pirate Queen, chieftain of the O’Malley Clan. She dominated the seas of northwest Ireland in the late sixteenth century. Traveling around this part of Ireland, I have been inadvertently tracing her footsteps, visiting all three of her castles along the coast, full of awe and respect as her legend seems to seep into many different histories of this place.

I have a full day on Clare Island and set out for a long walk, following the road as it dips into a small U-shaped valley with a tiny stream running through it. Suddenly, flanking both sides of the road among the sheep, there is an irregularity in the bright green, close-cropped grass: gray shards poking up out of the ground. They are not stone, but wood. These are Scots Pines that lived and were cut down 7,500 years ago, and as the climate and landscape changed, they were buried in the bog, where the acidity preserved them. Over the past 200 years, intensive peat harvest has brought them back to the surface once again. Experts think that the charcoal present on the stumps signifies that the earliest human inhabitants of the island felled the Scots Pines. The trees also appear to have been cut: they are broken off at about the same height above ground.

I pore over the stumps, counting the rings that are still visible, running my fingers over the bog-bleached wood, smooth as bone. I want to sit with them for a while, but I have a much longer walk ahead so I pull myself away. On the walk, I am disoriented, trying to wrap my mind around the concept of a 7,500-year-old clearcut. My mind is racing with so many questions: What, and when, is the Anthropocene anyway? When did it actually begin? Do these Clare Island tree stumps count? How could they, if they are so old?

Some think the Anthropocene began at the start of the industrial revolution, especially between 1800 and 1850. Others think it began around 1950 (clearly some rounding here), when nuclear weapons introduced their radioactive signature in the landscape. This time was also the beginning of the Great Acceleration—when the intensification of human activity and its negative consequences started to increase exponentially. Still others are of the mind that the Anthropocene—in the sense that humans became a geophysical force in the world—began in the mid-Holocene, when agriculture and its subsequent land use changes began, up to around 8,000 years ago. Still others argue that people caused the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna—and they will often argue against those who think the Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions were climate-driven. This is an enormous debate we won’t wade into here (spoiler alert: like most things, it’s likely a bit of both).

It’s easiest to think of the Anthropocene in a series of stages encompassing all of the above. The bottom line is that there is no clear beginning: humans have been slowly, and then not-so-slowly, increasing their impact on the planet for quite some time. Mid-Holocene deforestation coinciding with the dawn of agriculture lines up well with the Scots Pine stumps on Clare Island.

Even on Granuaile’s Clare Island in the 16th Century, descriptions suggest the place was at least partially wooded. But by the time the population reached 1,600 in the mid 19th century, it was completely treeless. Today, as grazing pressures lessen, willows are beginning to return. A new kind of rewilding is taking hold, one that allows nature to reconstruct itself based on whatever is at hand. This is not a vast reintroduction project, as I’ve come to think of rewilding in North America—it’s a primarily hands-off management scheme, and it has worked wonders on a small farm in the south of England, as I’m learning from The Book of Wilding by Isabella Tree. It’s an important and hopeful story that shows how a wild place can recover itself from intensive agriculture, given the chance.

During the Great Acceleration, England struggled to overcome food shortages for years after World War II ended. The government began paying farmers to fell and grind large oak trees to a pulp in order to create more farmland. It worked: the arable acreage doubled in less than 5 years, which shifted the landscape from small farm agriculture interlaced with its wild edges to large-scale, more uniform agriculture. England lost more of its oak trees during that time than it had in the previous 400 years.

But I’m not in England today—I’m in Ireland. As I join the sheep on my walks along the country roads, I notice the biological value of the hedgerows. These elongate biodiversity pockets are from where the only birdsong springs: the European Robins sing a tune that I cannot place in any other family of passerines that I know. As I walk along the hedgerows, I hear trickling streams running through them and poke my head into the vegetation, where I see mosses and aquatic plants growing near the water. For a moment, I think, maybe I’ll see a frog, then I remember that Clare Island has none, and may never have. The urge to introduce them (here they would be Rana temporaria, the Common Frog) lingers subtly in the back of my mind. This has, after all, essentially come to be my job in California.

The robins are gregarious they seem to come out and greet me. I try hard to get a good photo, or at least a recording of their beautiful song. I chuckle at myself, reaching my phone into a hedgerow, exerting so much effort over such a common creature, much like the visitors from elsewhere I’ve seen so excited about the squirrels in Yosemite. I’m sure the locals driving by are rolling their eyes at me. I love these robins too much to be embarrassed. Look at how beautiful they are.

Shortly after my arrival in Ireland but before leaving Dublin, I made sure to visit the Natural History Museum. I wanted to orient myself to recognize some of the wildlife that I might see while traveling around the country. Stepping inside, I was greeted with the old familiar scent of specimen preservative. Skeleton casts of now-extinct Irish Elk, with their massive antlers jutting skyward, greeted me as I passed through the threshold from the lobby into the long hall.

Wandering the cases, I pieced together similarities and differences between what I might find in Ireland compared to at home. There were few amphibians, but one stands out: an eel in a jar was preserved while in the process of swallowing a frog. The placard concluded that it’s because the eel choked and someone happened to come along and notice soon after it died. This is much less likely than the scenario in which the animal was caught and killed while it was attempting to swallow the frog. This distinction seems important. Perspective and questioning matter.

Like many places, the wildlife of Ireland has declined significantly in the last 100 years. The Irish Elk are reported to have gone extinct with the rest of the Pleistocene megafauna at the end of the last ice age due to a shift in climate (around 11,000 years ago). I wonder about humans’ role too. Signs at the exit assure visitors that the conditions for the “dead zoo”—as it’s locally known—are being improved and will be ready for renewed interest before too long. I am glad for this because it has already become a preserved world for Ireland’s now-extinct past—how much more will be left by the time it is finished? I hope that interest in the museum grows, and that in the process it earns a more science-affirming nickname.

New conservation and education initiatives in Ireland are encouraging. The following week, after returning via the ferry from Clare Island, I’m in Wild Nephin and Ballycroy National Parks in County Mayo. At the new visitors’ center—a bright, airy, modern space that seems to embody hope for the future—I learn about the unique biodiversity in the bog, river, and coastal ecosystems. Red deer are not native to Ireland, but likely escaped from farms/hunting reserves and are now naturalized, providing some of the ecosystem services a native ungulate would. A linear timeline exhibit journeys through the history of the whaling industry in the area.

It’s exciting to see new conservation activities just getting started: national parks managed for recreation and conservation, with interpretive signs not shy about stating the impact grazing has on the ecosystem, and their efforts to curb it. I still have a lot more to learn about the politics of grazing in Ireland, so I won’t wade too deeply into it, but what I’ve gleaned so far is that the EU implements conflicting policies: some that incentivize grazing, and other, smaller, newer, more tenuous ones that reward conservation practices like reducing grazing.

Evidence abounds that the tide is turning toward rewilding and conservation in Ireland. Eoghan Daltun has taken a 73-acre farm in Cork and turned it into an Irish Atlantic Rainforest, the subject of his new book by the same name. Even Trinity College’s stately Dublin campus recently turned its meticulously manicured lawns into native wildflowers to support pollinators.

The green spaces in the city support surprising amounts of biodiversity, as I noted in Saint Stephen’s Green, when a wave of relaxation came over me just listening to the birds in the trees as I took in the lush greenery. The day I left Dublin, Saint Stephens Green was named one of the top 10 most relaxing places in the world.

Crossing the Green late one afternoon, I saw a man feeding bread crumbs to the ducks and swans. A growing crowd of people was gathering to watch, and I was moved by the delighted looks on their faces as they experienced their nearness to nature. Moments like these—especially in an urban setting—are precious. The duck watchers could be conservationists in the making, if they aren’t already. They may be now more likely to vote for conservation-affirming politicians and policies. Feeding wild animals isn’t always the best idea2, but let’s check in for context: it’s a city park. What is actually happening here is much larger and more meaningful.

In addition to burgeoning conservation, Ireland has many enviable everyday sustainability practices. Even the KitKat wrappers are recyclable. The Irish potato chips (yes, crisps) tell you what varietal, county and even which farmer’s field the potatoes you are consuming come from. In the grocery store, it’s quite easy to purchase all of our food—even processed food like potato chips—from sources in Ireland or even nearby counties. We received a compostable bag for our groceries at checkout—and it’s durable! Efficient public transit is a dream come true. The tap water is safe and delicious.

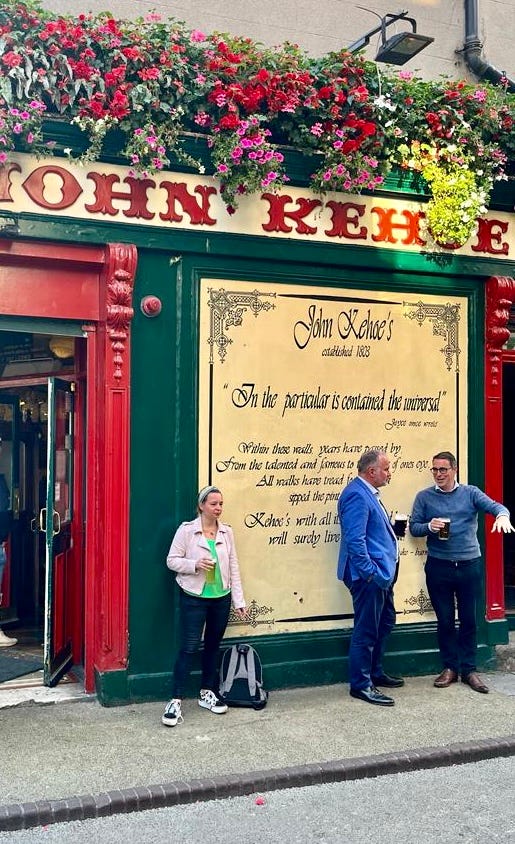

A dear friend’s brother took us on a whirlwind tour of Dublin the evening of our arrival. Near the end, he mentioned something in passing that has stuck with me: the buildings in Dublin are constructed in such a way that nearly all the streets can receive sunlight at some point during the day. I looked around, and I realized that this is one of the reasons why the city feels so inviting. The light nourishes the overflowing flower boxes on the windowsills of the stately pubs and warms the narrow cobblestone streets. What foresight for a city to recognize that its people need sunlight just as much as the flowers.

On Achill Island, I am delighted to find a new hiking trail—just established in 2015—honoring Granuaile and her history on the island, and spend an afternoon walking it until dusk. Sharing the walk, as always, with sheep, I still keep my eye trained on the ground out of habit for scat and tracks. The tracks are nearly always of sheep, though in Ballycroy we did see some Red Deer prints.

My eyes dismissively wander past a few unusual-looking scats, thinking an animal simply had a tummy ache. But when I see it a third time, it needs a closer look. It isn’t scat at all, but a European Black Slug. All of the questions come flooding in: is it native? Is it a lot like the banana slugs I know? Kind of. It is invasive in Australia and the Pacific Northwest, and some Canadian provinces, but is native to Ireland. Fun fact: they were used to grease cart wheels in Sweden in the 18th century. More importantly, they can be used to monitor pollutants because they easily bioaccumulate toxins in their tissues, much like filter feeding mollusks do in water.

The slug may seem like a miniscule thing not worth mentioning—compared to medieval frescoes or the majestic Irish Elk—but the fact that the simple application of curiosity can turn a turd into a wheel-greasing canary in a coal mine is marvelous. The truth is, there is nothing magical about travel: it’s simply plopping you in a new place so you have the opportunity to see the world with new eyes. It can be done at home, anytime. It just needs more concerted effort.

Visiting new places and experiencing new cultures and learning the histories from different places can be a lot of fun. It can also be confusing. Being new to this place, I’m probably getting some—or a lot—of things wrong, no matter how hard I try to get it right. Not helping things is that history is not one clear, definitive story: what surfaces in the present day as “history” depends largely on whom was doing the recording, and what they thought about it. We are never quite free from our own bias or that of our forebears.

Granuaile is a perfect example: in trying to learn more about her, I uncovered several conflicting stories. Many details of her life are foggy and walk the line between history, myth, and legend because most of what remains are stories that have been passed down for generations. Granuaile also led a life that had “overstepped the part of womanhood” at the time, so she was not always appreciated for her tenacity the way she is today. The best-preserved records of her life were unearthed by her biographer, Anne Chambers, in English state papers. These allowed her to separate some fact from fiction, but myths and legends still fill in the considerable gaps.

We will likely never know the whole truth—about the life of Granuaile, or the demise of the Irish Elk. The question remains how to live with what we do know, now, and do our best. Around 7,500 years ago, cutting down some Scots Pine trees was the Clare Island inhabitants’ best. Ireland’s efforts at sustainability have shown me what is possible when there is an honest desire to make things right. I know it’s probably not perfect. But it is quite enviable from an American perspective, when I see us squabbling over banning single-use plastic in California.

Rewilding efforts in Europe that are of the “remove the pressures and let nature take its course” variety are truly inspirational, coming from my perspective in a conservation community that tends toward more heavy-handed management. Of course, our countries’ continents and landscape histories are completely different and will have different needs. At the same time, the “less is more” approach is extremely attractive.

The Anthropocene has meant we will never go back to species assemblages as they once were at some magical, idyllic time in the past. Moving forward with what we do have is often the best, and most viable, option. Ireland and Britain seem to be getting this quite clearly, perhaps because they have been working with a much altered landscape—with species long gone—for quite some time. In North America, some of the losses we grieve may only be decades old, and if a few years of heavy-handed management can fix it, we should. But that doesn’t seem to be the way it goes in most cases.

Today I hiked along a river tinged a rich brown by the bog in Wild Nephin National Park, leaning into the gale force winds as rain whipped me in the face. It was the most fun I’ve had in a very long time—out in wild nature, with the sheep, being tossed around by the weather. I wondered if this was something like what John Muir felt when he climbed to the treetops in the Sierra in order to feel the power of storms.

Tonight, I’m grateful to be in a stone building as the wind howls in the hedgerows outside and I sit warming my feet by the peat fire. Even in a landscape that has been significantly and irrevocably altered by human hands for millennia, there is more than ample opportunity to experience wildness and a way to reclaim a meaningful relationship with nature here. I’m eager to watch as Ireland navigates its rewilding efforts, and what we in North America can learn from them.

Have you heard of Granuaile? Do you have European Black Slugs invading your yard? Do you know of a rewilding project near you? Have you experienced different sustainability practices in a place you don’t live? Did anything spark hope in your life this week? Let us know in the comments!

Indigenous people of North America have been present for thousands of years and continue to have a significant and important relationship with the land to this day. As just one example, the Cahokia Mounds in Illinois provide a window into the ancient history of humans in North America. I encourage you to learn more about indigenous lands, treaties, and languages of different places.

It’s worth noting that bread isn’t the healthiest food for waterfowl, but there are alternatives.

Love this, Andrea! I was there with you every step of the way through your amazing descriptions blended with scientific and historical knowledge. The images are great too. Thanks for what you do.