Start Here: The Hopecology Explainer

The ongoing environmental catastrophe leads many to despair, but hopelessness precludes the attitudes that can lead to meaningful, changemaking action. Hopecology is a study in looking unflinchingly at the stark realities of the present, while also returning focus to the natural world that will literally save us, if we are to have any hope at all.

First, definitions.

Hope + Ecology = Hopecology.

According to the Internet on this date, the word “hopecology” does not yet exist. The search engine asks me if instead I mean hip hop ecology, which is great because now I’ve learned what that is and I’m glad I live in a world where it exists.

Literally the study of the place we call home (from the Greek Oikos, meaning “household”), the discipline of Ecology focuses on the natural world and the relationships within and between the disparate parts we have broken it down into: animals, plants, fungi, minerals, processes (such as the water cycle).

The Merriam-Webster definition of “nature” includes “the external world and its entirety,” meaning: NOT US. Paradoxically, recovering our inherent connection to nature is precisely what is going to assist us in dealing with the desperate state of planetary affairs we currently find ourselves in.

Though the term “ecology” is now more broadly used to refer to relationships between any number of things (for example, “information ecology”), this trend signifies a hopeful cultural evolution toward a focus on relationships, whether nature-based or not.

What’s more, the broader definition is useful here, because Hopecology will discuss relationships (to ourselves, to each other, to new or old ideas), but not necessarily always from the perspective of the discipline of Ecology.

Who is writing this

I am Andrea Joy Adams, a conservation ecologist and writer. I research solutions to the biodiversity crisis—the rapid rate of species disappearing. I’ve been working on the front lines of biodiversity decline for over twenty years. I study one of the most threatened groups of species on the planet. I am no stranger to despair.

Working in the crisis discipline that is conservation biology, it has been my job to unearth just how bad we are mucking up the planet and try to figure out ways to slow down the stolid march of biodiversity decline.

Fortunately, many others seem to be waking up to these harsh realities, too, creating an unexpected shift in my role as a scientist. I went from collecting data in order to be able to say,

“Look! Over here! These things are really, really bad and it is totally our fault and it’s time to fix it! HELP!”

…to nowadays finding myself saying,

“Hey, WAIT! Well, no…it’s not quite as bad as you describe, but it could be. And yes, these problems are real…but there is still time to make a difference. No…you don’t have to throw in the towel! I know it’s hard! Don’t give in to despair!”

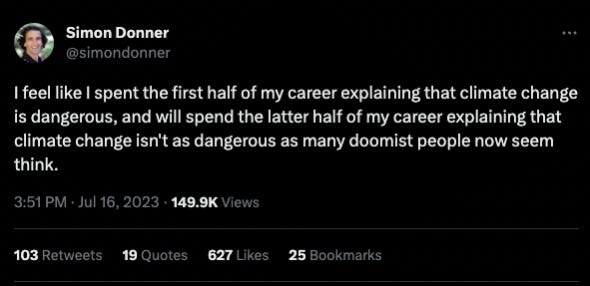

I thought I was the only one who felt this way, until I came across a climate scientist’s tweet expressing much the same sentiment:

(If you’re interested in the thread, you can check it out here, but the TLDR version is that detractors of this statement argued, loudly, for hopelessness, saying, “But the situation IS hopeless!” This attachment to suffering is a post for another day.)

For the past twenty years, I’ve been trying to figure out how to live with the gravity of what we’re dealing with. But many others have been forced to come to terms with it just in the last few years.

Even ecologist Aldo Leopold wrote about the lonely weight of distressing ecological knowledge nearly 75 years ago:

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise.”

So, if you’re new to the party, WELCOME!

Also, I’m sorry for your loss.

Fortunately, there are all kinds of resources for dealing with ecoanxiety and despair. What I see missing from many of these resources, however, are antidotes to what caused the problem in the first place. Solutions to ecoanxiety and its resulting despair are primarily focused on how to address it as the mental health crisis that it indeed is. This is great because mental health is paramount and foundational. But we can’t stop there.

Why I started Hopecology

I think a lot about hope: why we lose it, how we regain it, and its ebbs and flows that cycle through us. I started Hopecology because I’m living the question of how to stave off persistent despair in a perennially, epically, terrifyingly changing world, and I know I’m not alone.

Ecologists are not nearly as common as real estate agents in the general population, so I am often approached for my expertise on subjects related to nature and the environment by strangers and acquaintances alike. The questions have evolved over time but all have a common thread of despair or confusion:

2020: “I heard the pandemic ended climate change. Is that true?”

2021: “What can I do that will make a difference? Nothing seems like enough.”

2022: “Why would I care about wildlife? What is it doing for me?”

2023: “I really want to talk to you more about what’s happening with the wildlife on our beaches. It’s just tragic.”

Understandably, people want me to help them feel better, whether through recommendations about what they can do to help, to reassure them that everything isn’t as bad as it seems, or to tell them whom to blame. They want to know that there is something—anything—they can do to help themselves and the planet, even if it means just aiming their anger and frustration in a specific direction.

I’m familiar with these sentiments. I’m also no stranger to the fallacy that I can buy my way out of the problem (by the way, if this worked, the planet would be squeaky clean and forever healed).

Somehow, I have (so far) managed to find my way out of each dip of despair—not through empty platitudes or false hope; but through the direct experience of nature itself.

The truth is this: we do not know what the future holds. The false propaganda of despair is that it operates on the assumption that we do. We can have hope because we literally do not know what will happen next, and that is a good thing. As historian Howard Zinn wrote,

“I am totally confident not that the world will get better, but that we should not give up the game before all the cards have been played.”

In the meantime, we can look to the nature all around us, where our feet are, take a deep breath, and do what is right in front of us today. Some days that will be as simple as looking squarely at the hand we are dealt. This takes an act of courage.

What Hopecology is not

I’m not going to tell you that things aren’t bad, that climate change isn’t real, that it’s not our fault, or that nothing can be done about it—because none of these are true.

I’m also not going to tell you which products to buy, whether or not to go solar, or whom to blame (okay, I may tell you whom to blame sometimes).

And I’m most definitely not going to try to instill false hope that everything will be okay. Because we don’t have evidence that it will. Yet herein lies the rub: we don’t have evidence that it definitely won’t either. One thing that will ensure it won’t? Giving in to our despair.

As Aldo Leopold wrote to a friend,

“That the situation is hopeless should not prevent us from doing our best.”

I can’t promise you that you will find hope here. The journey to finding hope is as unique to the individual as a fingerprint—it’s an inside job anyway. But I do invite you to explore the topic in this community.

What Hopecology Is

I’ve noticed that, often, a sense of hopelessness about the environmental crisis comes from misunderstandings about the natural world. Therefore, an aim of Hopecology is to be simultaneously exploratory and educational.

The scientist in me appreciates the elegant simplicity of breaking down nature into patterns and processes to help us better understand our planet and what we’re doing to it. The rest of me sees a need for more: science provides us with information, but it’s up to us to decide what we do with that information and what it means. Science is great at taking us down the rabbit hole, interrogating deeper and deeper questions into the mysteries of the universe. There are, however, some mysteries that science just can’t answer.

Like its portmanteau name, Hopecology wades into the estuaries where science and the mystery mix. It’s a risky business, because the line between pseudoscience (i.e., the result of combining scientific-based information with wishful thinking) and pushing the interdisciplinary edges of knowledge and understanding can get a bit murky. But that’s what makes it interesting.

Posts will blend perspectives on academia, relating to the natural world, conservation, ecology, and philosophy. I don’t shy away from asking hard questions, even if it means being critical of culture, especially academic culture. Occasional, more personal posts delving into tough topics, such as mental health, will be for paying subscribers only.

It’s breaking out of misleading assumptions about the ways in which we try to understand the world that will help us get to the territory where hope can be found. I hope you’ll join me.

Love this! Thanks for being here. Here's another great Zinn quote: “To be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is a history not only of cruelty but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage, kindness. What we choose to emphasize in this complex history will determine our lives.”

I just absolutely love your theme you are riding right in middle of the trail